Kentro Connection

Caring for creation is grounded in the reality that we are made in God’s image

By J. Marc Foggin – Plateau Perspectives (7 min read)

We are relational beings, lovingly made in the image of the triune God of grace.

When we see and understand the world as God does, recognizing how much we depend on other creatures to eat, breathe, and flourish, then at a most fundamental level this affects how we relate to God, to others, and with the rest of creation. Whether we recognize it or not, how we see the world – how we see nature and other people – affects the choices we make, probably all the choices we make.1 But all too often, we assume that the present way of doing things, how we choose to live our lives both personally and collectively, is the only possible way. We wrongly perceive, or believe, that nature is mostly just a resource to be used and that the value of things is summed up in their monetary value – yet this is so far from the truth.2 Instead, the most important aspect of life is relationships – relationships between people, between people and nature, and with God in whose image we are created

Why are relationships so important? First, we are created in God’s image, and God is triune – Father, Son, and Spirit. And second, we are embodied creatures that depend on countless seen and unseen fellow creatures to sustain our daily living. Whether we look through the lens of ecology or theology, it is our belonging as part of a wider community and our manifold relationships that ultimately define us!3

Our very essence, then, is relational; but we have lost our way, we have forgotten who we are, and for innumerable generations we have sought to be the masters of our own lives – with too little concern for the lives and wellbeing of others. But as J.B. Torrance has made clear, in the Christian doctrine of the Trinity wherein we understand that the very being of God is loving communion, “His primary purpose for humanity is filial, not just judicial – we have been created by God to find our true being-in-communion, in sonship, in the mutual personal relationships of love.” And, as Torrance writes, “What is needed today is a better understanding of the person not just as an individual but as someone who finds his or her true being in communion with God and with others. […] God is in the business of creating community.” Furthermore, the natural world is not only the ‘theatre’ in which our human story unfolds, but it is God’s creation, which He has declared unambiguously to be good – this being the ultimate source of its value! – and He has commissioned us to give ourselves in service, to be loving stewards and caretakers of creation, to know and faithfully tend all that He has made – for the flourishing of all life.

Our aim, then, is not simply to get what we can out of nature for personal benefit, even if done sustainably. Nor is it to turn a profit at the expense of others, as all that has been made by God and offered to us is for our common good, as we in turn also give our lives in service to others. In the end, the essential work that God has called us to is not to create a sustainable world as much as it is for us to build “a more beautiful, healthy, vibrant, diverse, clean, fragrant, delicious, and just world.”4

As the new executive director of A Rocha USA, Ben Lowe, has said, “Caring for creation is an integral part of loving God, neighbour, and the rest of God’s world. This has always been the case. […] I care for creation because I follow the Creator, and I feel a particularly urgent calling to contribute toward restoring right relationships and mutual flourishing…”5

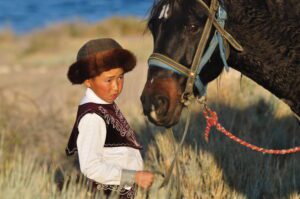

How does this translate into action? In our own work, Plateau Perspectives is partnering with several mountain communities who live in a remote valley in Central Asia to empower them, help give them more voice, strengthen partnerships around common purposes, and rebuild livelihoods with a renewed sense of community in a place where much has been lost over the past several decades. It has been a very long winter for this mountain community, which was forcibly relocated to the lowlands to engage in agricultural labour. Yet, even though for a time they endured extreme physical hardship, what has been felt most deeply is the sense of progressive loss of their culture. What they wish most is to maintain a sense of their cultural identity – this being not only about shared history and common identity expressed through stories, practices, and beliefs, but equally concerned with a sense of future and common direction, hopes, and aspirations. Cultural continuity has deep significance for everyone, for no one is simply an individual, or just a material body, any body; just anybody. Rather, each of us is special and unique, and always we are members of broader community.

Now, more tangibly, while the capital city is already reaching high summer temperatures, signs of spring are coming forth in the mountains; but they are exhibiting now more as danger and damage. Warming temperatures are bringing avalanches and landslides long before the arrival of new growth in the alpine grasslands. Still today the roads are blocked and people’s access to the valley is limited to travel on foot. This may continue for another month, possibly longer; travel in or out of the valley where our project is centred is severely limited for at least six months each year. That being said, the local community still wishes to live there, in that valley, their valley, as the land, water, and wildlife, along with all the special crops and livestock that are well adapted to this mountain environment – in essence, all of biodiversity, all of creation – constitutes so much more for them than just ‘resources’ to use. This valley is their home.6

The project we are now launching aims to strengthen a recently established national park, especially ensuring that the park authorities remain focused on the interests of communities – recognizing them not as a problem, but rather as a central part of any solution! And just as we previously engaged with nomadic communities on the Tibetan plateau a few years ago,7 here, too, we are seeking to build partnerships and to restore relationships.

Specific project activities will include snow leopard surveys with camera traps,8 developing a network of community monitors, education and awareness programmes, offering new ways for ‘mountain voices’ to be heard (such as a participatory video project), strengthening the development of community-beneficial tourism,9 as well as organizing workshops on “community co-management” for the newly established national park and a study tour to visit Canadian parks or nature reserves that have much to offer us in regard to what is being learned through the emerging partnerships with a wide range of First Nations.

This suite of planned interventions exemplifies at least in part how seriously we are taking the dual imperatives to care for creation and work for justice in all its forms. Further, these two core aspects of living in God’s kingdom now, “on earth as it is in heaven,” are so tightly interlinked as to be virtually inseparable, with both having at their core the restoration of relationships.

Another area of work in which Plateau Perspectives engages is in matters of “sustainability” – what does it mean, what are its fundamental pillars, what are our responsibilities as Christians? And, recognizing that something is missing in the concept of sustainability – where should we look? what needs to be added?

While the basic underpinnings of so-called sustainable development are good – there are many important principles highlighted, for example, in the Sustainable Development Goals or SDGs – we have nonetheless, by and large, simply continued to value ‘economics’ over and above the two other main pillars of sustainable development, namely the ‘environment’ and ‘society’. We see this in changed framings, as while we once would have asked ourselves about any new idea or plan if it were “good for society,” now we only ever hear the question “Is it good for the economy?” But the theory or belief in “trickle-down economics” has long been disproven if not actually displaced in practice. It is a false story that we once told ourselves; it is time to relegate it to myth, a widely held but false belief or idea. Inequalities are everywhere. Jesus taught us to pray for “our daily bread,” not for accumulated wealth to last many lifetimes.

Clearly, as Irish President Michael Higgins says, much of the social science that we know as economics “has lost touch with everything meaningful” and “no longer is connected […] with the social issues and objectives for which it was developed over centuries.” As Higgins continues, we urgently need to “rebalance economy, ecology and ethics.”10

One of the main problems is that as we consider the ‘human dimensions’ in our pursuit of sustainability – lofty as it is for us all to not overuse resources, or to harm people or nature – we only ever hear about society in a somewhat vague sense, being comprised of individuals and key measures of success being exclusively assessed on a per capita basis. But this does not take into account the reality that we are created in God’s image and thus we are persons, that is, relational beings. Yet, we are generally conceived and treated only as individuals, each one of us disconnected from all others – our relationships are missed, forgotten, overlooked… What we need now is renewed understanding of who we are and our relationships in broader community. We have lost our appreciation of the deep value of community, and our calling to work for a common good on a shared earth. These need to be restored. Even a former chief economist at the World Bank, Joseph E. Stiglitz, suggests that the solution to the inequality crisis we see present all around us “lies in focusing on community rather than simply on self-interest – both community as a means to prosperity and as a goal in its own right.”

Even more so, when we remember that God created us as beings-in-relation – we never have been “just individuals” – and that He created us for community, to live and participate within the loving relationship of the triune God who is Father, Son and Spirit, then we will realize, too, how much we need to reorient our individual and collective lives so as to live as we were created to be – in God’s image, others-centred.

Finally, we are not only members of human communities, but part of God’s wonderful creation, of the entire community of life. It will be, at least in part, in the recovery of a sense of our createdness together with all of Creation that we will begin to value all of life as God does. Moreover, God not only created all things, statically, at some point in time in the distant past, but even today, dynamically, He sustains all things! “For by him [Jesus] all things were created: things in heaven and on earth, visible and invisible […] and in him all things hold together” (Colossians 1:17, emphasis added). As mirror to God’s concern and indeed His love for all that He has made, we too – being created in His image – are to concern ourselves with and to love all that He has created. We are to build up life, not diminish it. And the fullness and vibrancy of our lives hidden in Christ and all life renewed in Him is what Spring reminds us, year by year.

Footnotes:

1 See Mace, G.M. (2014). Whose conservation? Changes in the perception and goals of nature conservation require a solid scientific basis. Science 345: 1558−1560; Bookless, D.J.C. (2019). Why should wild nature be preserved? A dialogue between biblical theology and biodiversity conservation. Doctoral thesis, University of Cambridge; and Foggin, J.M., D. Brombal, A. Razmkhah. (2021). Thinking Like a Mountain: Exploring the Potential of Relational Approaches for Transformative Nature Conservation. Sustainability 13(22): 12884.

2 See Eisenstein, C. (2011). Sacred Economics; Money, gift & society in the age of transition. Evolver Editions; Stiglitz, J.E. (2012). The price of inequality: How today’s divided society endangers our future. W.W. Norton & Co.; Wirzba, N. (2021). This Sacred Life: Humanity’s Place in a Wounded World. Cambridge University Press; Morrison, S.D. (2023). All Riches Come From Injustice: The Anti-mammon Witness of the Early Church & Its Anti-capitalist Relevance. Beloved Publishing; and Metzger, P. (forthcoming). More Than Things: A Personalist Ethics for a Throwaway Culture. IVP Academic.

3 See Torrance, J.B. (1996). Worship, Community, and the Triune God of Grace. Paternoster Press.

4 See Wirzba, N. (2023). The Trouble with Sustainability. Sustainability 15(2): 1388.

5 See https://arocha.us/meet-ben-lowe.

6 As rightly noted by Wirzba (2023), we should be cautious about our use of the term “natural resources” since this diminishes living creatures and places to mere objects. Likewise, the “environment” is so much more than just resources, it is our very home. Two of the six recommendations that he proposes for shifting our language, and in this way aligning ourselves more closely with God’s view and His way of interacting with the world that He lovingly created are: “Drop the language of ‘natural resources’ [as this] designation [wrongly] assumes that living creatures and vibrant places are collections of objects that are without value until we assign them one. [Even] tabulating ‘ecosystem services’ in terms of monetary value […] risks violating the sanctity of life”; and secondly, “Replace ‘environment’ with ‘home’, since this is the more accurate description of where people and creatures, in fact, live. An environment is simply what ‘surrounds’ us and, thus, is not integral to who we are and what we can become. Homes, by contrast, are essential, dynamic (though not always pleasing) places of nurture that require our respect and care… [It is helpful to] recall that the word ‘ecology’ has the Greek root oikos, which means ‘home’.” In similar vein, the Mayi Kuwayu Team recently noted in their article Promoting planetary health through culture published in The Lancet Planetary Health the extent to which “land, culture, and health are inextricably entwined in many Indigenous societies [and how] relationship to country [or land, territory] defines identity, kinship, and language group, and permeates every aspect of health and wellbeing.”

7 See Foggin, J.M. (2018). Environmental Conservation in the Tibetan Plateau Region. Land 7(2): 52. Also see Foggin, J.M. and Torrance-Foggin, M. (2017). Pastoralism, Development, and the Future of Tibetan Rangelands: Experiences in the Development and Provision of Social Services and Environmental Management, Chapter 13 in Tibetan Pastoralists and Development: Negotiating the Future of Grassland Livelihoods, Reichert, Germany. More information is available on Plateau Perspectives’ website and in a recent photo story about their work.

8 See Foggin, M. (2012). Pastoralists and wildlife conservation in western China: collaborative management within protected areas on the Tibetan Plateau. Pastoralism 2, 17. Also see online report, Tibet snow leopard project gets locals involved, as well as Plateau Perspectives webpages on snow leopard and co-management.

9 See the photo story Choosing Ecotourism in Kyrgyzstan and the related documentary video The Future We Want. A summary report about the development of community ecotourism is found here and here.

10 Leahy, P. (2023). President condemns ‘obsession’ with economic growth. The Irish Times, 28 April 2023.

Collaboration is at the center

Organizations can’t fight poverty on their own. Get connected. We are stronger together.